Messi Madness in New York City

It was a privilege to witness our Michael Jordan go to work. But what does it all mean for Major League Soccer?

A blind man came to see Lionel Messi. He had his white-and-red cane in one hand, his other arm locked in a companion’s as they walked along the black cement of the concourse amongst the myriad concessions stands at halftime. Was she a fan, and he just came along? Or was he here to let the oceanic roar of the expectant New York crowd wash over him — to bear witness in his own way?

After all, Gretzky was in town. The Michael Jordan of our moment. Messi brought his merry band of La Liga legends to Queens, and they did not disappoint. Sighted or not, everyone here glimpsed something special — and increasingly fleeting — as NYCFC were condemned to sporting destruction by Inter Miami. Messi inevitably played judge, jury, and executioner, and many of the New Yorkers here had come to Citi Field hoping to see exactly that kind of punishment handed down to their hometown team. Not everybody, though.

“Oh yeah? You brought ya kids?” said a wide-set man in NYCFC sky blue as he trundled down the steps towards his seat a few minutes before kickoff, eyeing everybody in pink and black. “Fuck outta here.”

This section to the left behind one goal, down the third-base line if the New York Mets were playing, was about half NYCFC stalwarts. I could hear folks chattering about the season so far, or complaining that the double gin-and-tonic they’d ordered here was weaker than a single at Yankee Stadium, the club’s more regular home court.1 As the stadium announcer read the starting lineups, they shouted out every name and booed the Miami ones. Diagonal across the field, in the right-field stands, fan groups like The Third Rail banged on constantly throughout the game, singing songs about their players and the club.

But there was a whole row of 10 or 11-year-old kids behind me in black or pink Miami shirts crying, “Messi! Messi! Messi!” even before kickoff. At one point, while I was taking in the scene before the match from higher up on the concourse, a grown man behind me went, “Messi! Messi! MESSI! MESSI! MESSI!” He was almost pleading for the great man to come out and for the match to start and for it to all be really real. A crew of five more grown men, all together in matching black Messi #10 kits, were lined up at security when I arrived at the stadium gates.

To be fair, the walk there from the Long Island Rail Road stop was nothing like all that. There were just a couple of Miami shirts sprinkled in with the NYCFCs and the rest of us unaffiliateds. I’m a native New Yorker, but I find it hard to connect with either of the city’s pro teams in this sport. An energy drink in New Jersey or a team linked to Manchester City? It’s not much to choose from.

I’m very much affiliated with New York, however, and it gave me joy to walk the wood slats of the boardwalk-style elevated walkway from train station to stadium, past the vendors selling “Cold beer!” and water out of coolers on the ground in front of them, others hawking Messi kits that were surely 100% authentic. Some of the accents I heard were absolutely the genuine article, and things only improved once I got inside the stadium and the pregame DJ served up a regular diet of Ja Rule and Fat Joe. And when Miami finally came out for their pregame warmup, long after their opponents had taken the field, the villainous out-of-towners were greeted with an eruption of boos.

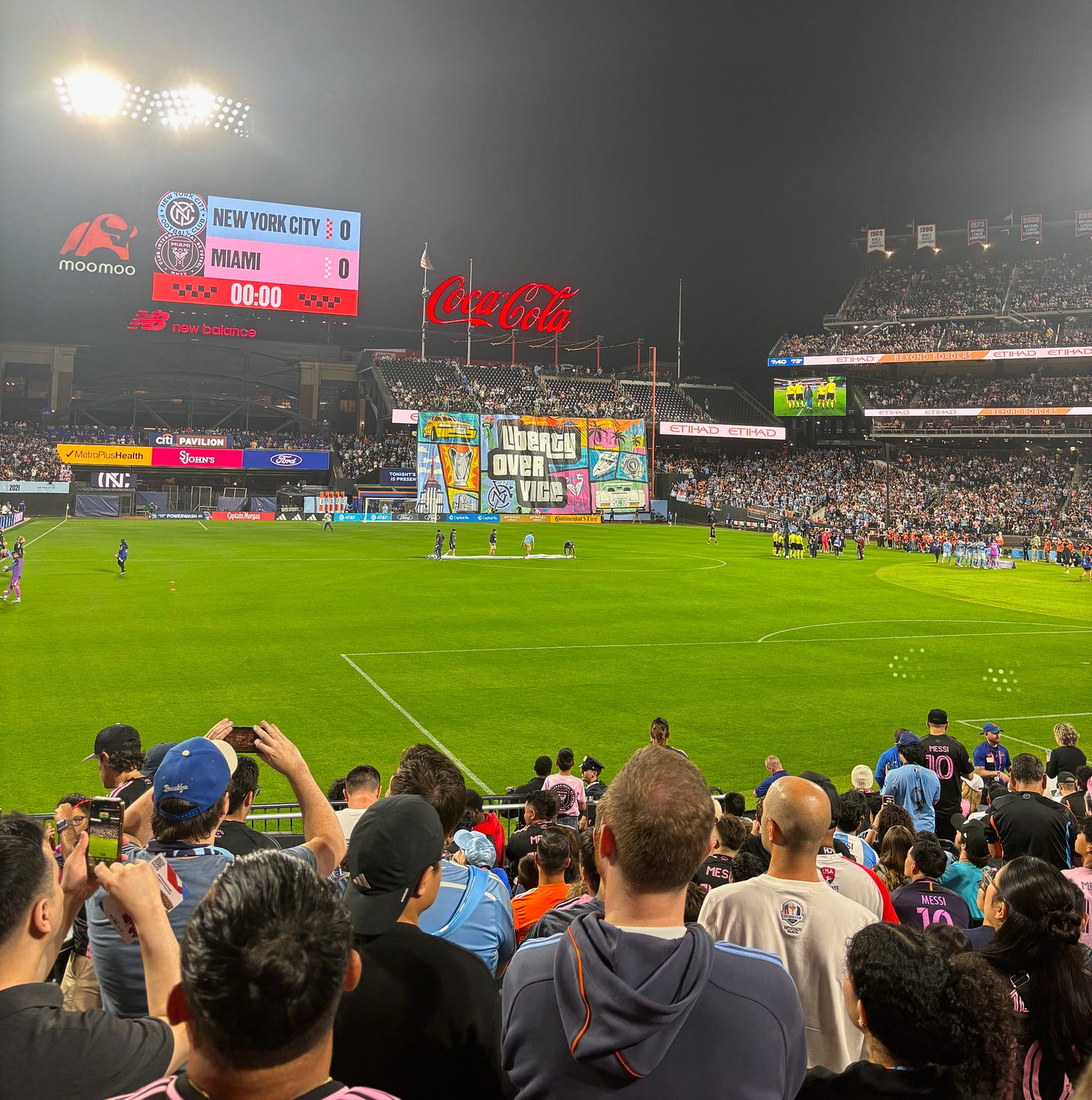

After the pregame festivities finished and the “LIBERTY OVER VICE” tifo unfurled out in right field2, the match kicked off, and NYCFC had more than a foothold in the first half. Miami rarely troubled the home team’s U.S. international goalkeeper, Matt Freese, and it was the #7 in blue, Nicolás Fernández Mercau, who went crashing in behind the Miami backline on 29 minutes. He turned a defender inside-out and smacked the post.

But even on the back foot, Miami showed their class. Jordi Alba was motoring up and down the left, and Messi nearly found him in behind the NYCFC defense with some glorious touch on a chipped pass. Sergio Busquets3 was peerless in midfield, demonstrating in real time the difference between professional players and the all-time greats. Watching him waltz through the blue shirts, scarcely breaking a sweat, I was reminded of sitting in a high-school gym in Latvia while reporting a story on Kristaps Porzingis, watching his NBA friends scrimmage with his old buddies from Spanish pro ball and seeing the levels. No wonder Riqui Puig, a star in Major League Soccer, once told me, “I’m going to explain to my sons that I played with Busi.” He’d turn away from two or three markers at a time with a trademark drag-back or chop-turn before spraying the ball to the outside or through the lines.

It was one of the latter line-splitters that opened up the scoring, except it came from the #10 in black after Busquets found him in a pocket of space between New York’s midfield and defensive line. Messi took it and turned in one motion, letting it zip across his body onto his left foot as he swiveled to face a defender who’d left the line to confront him in space. That turned out to be a poor decision: Before Thiago Martins could get set, a through ball was through his legs into the gap he’d left for Miami’s Baltasar Rodríguez to run into. The 22-year-old Argentine latched onto his compatriot’s perfectly weighted ball and slotted it past Freese.

It was a couple of minutes before halftime, and Citi Field blasted off, though it wasn’t all raucous applause. There were plenty of boos, too, and earlier in the half, there were some mocking cheers — the kind of “Heeeey”s you hear from English fans — when Messi’s poor touch near the sideline sent the ball out of play. At times, the rising chants of, “Messi! Messi!” were met in vocal battle by, “NYC! NYC!”

There clearly was a real fandom here. Every stadium announcement was bilingual in a nod to the nature of the NYCFC supporter base, and the stadium camera — transmitted to possibly the largest screen I’ve ever seen out in the center-field stands — seemed at pains to avoid showing the man himself, as if to declare this was about more than just him. But the proof is in the numbers: 21,764 was the average NYCFC attendance in 2024, per Hudson River Blue. 40,845 were in the building for this one.

There were the masses in Messi Miami shirts, of course, but others committed the cardinal sin of American soccer fandom: the random kit. Thomas Müller may be in MLS these days, but his Bayern Munich jersey was hardly appropriate for this occasion. I love Martin Ødegaard as much as the next guy, ma’am, but come on now. As cringe as those vestments might have been, though, they were testaments to the sports-historical character of the event: It was a night for football fans. It was a night for anybody who wants to bear witness to something, to say they were there.

In his golden years, Lionel Messi mostly has a languid stroll around the center circle when his team are forced to defend their own box. When an opponent ventures near him with the ball, he manages to put in just enough effort in his challenges that he’s not mailing it in — but not enough to put himself in harm’s way. That’s not what he’s here for. He’s here to put on a show, and even when he’s scarcely moving, the head is on a swivel. He’s mapping and re-mapping the field, his teammates, his foes, the space, the opportunity.

On 60 minutes, it began to rain down thoroughly. Not a downpour, but certainly a drench job. It was 1-0 already, but only now was the stage truly set.