What Everton Will Leave Behind at Goodison Park

Ahead of the last Merseyside derby at Everton's home since 1892, a requiem for "the last of the great signature old stadiums."

By the time Iliman Ndiaye played a smart one-two with Idrissa Gueye and scampered in behind the Tottenham midfield, driving at their backline until he hit a swift stepover at the top of the box and smacked one high in the net to make it 2-0, the Gwladys Street End was bouncing. The roar of the Everton faithful caromed off the ancient girders and wood and concrete, just as it had when Dominic Calvert-Lewin turned the Spurs defence inside-out and slotted home the opener in the 13th minute.

On both occasions, I had to crane my head around a royal blue pillar—and the cresting waves of others’ heads and limbs in front of me—to see what happened. From a seat deep in the stand behind the goal, under the overhang of the second tier above, you could still just about see events at the far end—where Everton were banging in their first-half goals—if you found that sweet spot, that letterbox window through the madness. I wouldn’t have had it any other way.

This is life in the back of the Gwladys Street, the beating heart of Everton Football Club’s home support. And it’s life at Goodison Park, their idiosyncratic base since 1892 where around 10 percent of the seats have Obstructed Views, and where time is running out.

After the Merseyside derby on Wednesday, Everton have just six more games to play in this famous old ground where Pelé and Garrincha and Franz Beckenbauer scored World Cup goals in 1966, where Eusébio scored four to help the Portuguese storm back from 3-0 down against North Korea, where Dixie Dean scored his 60th goal in a single season of top-flight football, where Everton staged eight campaigns that ended with English first division titles. This summer, the Blues are moving house.

“For me, Everton will always be Goodison Park,” said Rob Sawyer of the Everton F.C. Heritage Society. “But I recognize that for the younger people in particular, we've got to move to somewhere fit for the 21st century.”

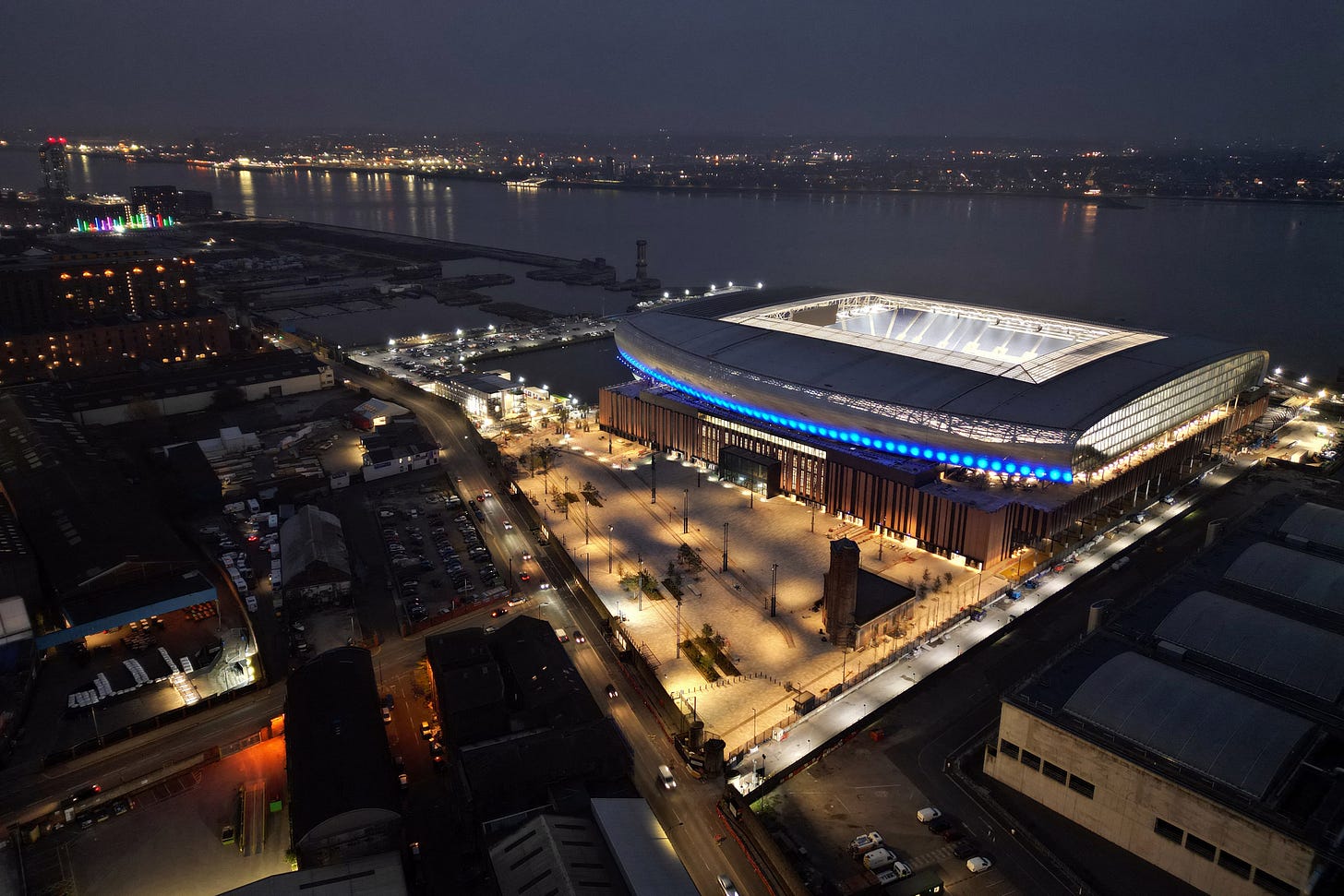

That somewhere is the Bramley Moore Dock, where the shiny new Everton Stadium now lies in wait, just about finished after years of development that began with purchase of the land in 2017 and planning permission approval in 2021. With a capacity of close to 53,000, the club’s hierarchy—and its fans—hope it will deliver the revenue and the grandeur to make Everton a major European club again. They want to stage European tournament finals, perhaps the Europa League or the Conference League to start. Fans of their mostly amicable local rivals, Liverpool, may have to watch superstar musicians play concerts at Everton. The blue side of Merseyside want to be somebody in this brave new world of football, but it will come at a cost.

Goodison Park is in a church’s backyard. Back in the day, fans would climb up on the roof of the worship house to earn a free ticket to watch the Blues play. It’s called St. Luke’s Church, and on matchdays, upstairs before kickoff, you’ll find a collective shrine to Everton Football Club. There’s a cast of characters who operate different stalls featuring classic kits, old match programs, historic memorabilia, and—in their proprietors—a whole lot of knowledge.

Richard Gillham, who goes by Richie, operates a stall in the back right corner. He is secretary of the EFC Heritage Society. He stands behind a table arrayed with books with names like Goodison Glory. Above him to the left, there are baseball jerseys from the New York Giants and Chicago White Sox, who once played America’s pastime at Everton’s ground back in 1924. Everton players got involved in a baseball league during the Second World War, he mentioned, and Goodison also played host to an American football game featuring sailors who were stationed in Liverpool. Among them on the USS Leviathan was Humphrey Bogart, though it’s not confirmed he took part in the game. What is for sure is the final score.

“Only Everton could have a nil-nil American football game,” Richie said.

When he was a kid, he used to go to the enclosure at the front of the Main Stand with his dad, and a friend of his dad’s would bring along “the bottom three rungs of an aluminum ladder” for him to stand on so he could see. The enclosure was terracing then, all-standing, and young Richie needed a leg up over the adults.

So did Roger Bennett, the Evertonian romantic at the heart of the Men in Blazers. Over the phone after my visit to Liverpool, I asked him if he remembered his first match at Goodison. “Yeah,” he said. “April 1, 1978. Everton 2, Derby County 1.”

His dad waited until he was six and brought him to a morning kickoff for “a safer, more prudent introduction,” Bennett said. “It was a freezing day, and it was a slightly more violent era. I was just a kid, I didn't really realize what was going on, but I would say it was quite an energetic walk from the car to the stadium.”

———————————

It takes resources to report stories like this on the ground at football’s greatest venues.

If you’re enjoying this one, consider subscribing — for the price of a pint, you can help make more of them happen:

———————————

There wasn’t much live football on back then, and Match of the Day was on late, so Rog grew up listening to Everton games on the radio. He’d scarcely seen the Goodison pitch outside of newspaper photographs.

“I just remember it being so green, and so startlingly beautiful,” he said. “And the amazing thing is now, when you look at football pitches in the 1970s and 80s, they weren't that green. They were mud piles. But, like, genuinely, it was like the greenest dale I had ever seen. It was stunning and it was beautiful and it was freezing and I couldn't see.

“Everyone stood up around me, grown men, so I couldn't see anything. And the memory I have is that the stranger to my left saw that I couldn't see a thing, and he just lifted me up with one hand, took off a giant jacket that he had on with the other, turned it into a bundle and just plopped me back down on top of his coat. And he goes, ‘Oh, we’re one big family here at Goodison.’ And he stood there in the freezing cold in his T-shirt for the whole game.”

A day out at Goodison was a rougher one in those years. Going to the football was a harsh—occasionally terrifying—experience. But there was warmth in it, too, and Everton were good. Richie was there for the famous Cup Winners’ Cup victory over Bayern Munich in 1985, “one of the greatest nights ever for atmosphere” at Goodison. Back in the day, the attendance could top 60,000—the record was 78,299 for a Merseyside derby in 1948—but then there was Hillsborough, and the Taylor Report in 1990 mandating that English grounds become all-seater.

“I prefer standing, because I think it creates more atmosphere,” Richie said. When I met up with him downstairs at St. Luke’s, Rob Sawyer said the same when I mentioned my seat was in the Gwladys. “In all stadia, it's lost a little something. But you'll enjoy it. You'll feel the history in the wooden beams, the concrete. You’ll love it in there.”

Down Gwladys Street, there’s a row of houses on one side that’s typical of the blocks all around Everton’s castle, a line of modest rowhouses in an array of colors: pale blue, red, gray, your occasional yellow. At the end of the street, it’s Stanley Park, the sweeping greenspace that separates the Evertonians from the Reds at Anfield. And on the other side of the road, across from the rowhouses, there are the many numbered entrances to the Gwladys Street End.

With a scan of your ticket, you crank through the ancient turnstiles—clank-clank—and arrive in the concourse under the soaring ceilings supported by still more blue beams. This is where the faithful gather at halftime in groups of two or three or four, slugging a pint or two before the 15 minutes are done. They might lean up against a wall or a girder, blue-and-white-scarves peaking out from beneath black winter jackets as they chat about the triumphant return of manager David Moyes and the old-new-boss’s tactics, or stories (and complaints) from the past week at work, or—in the case of this Tottenham match—whether Ange Postecoglou could lose his job over this. After all, he’s losing 3-0 to Everton at the half.

But before that, before it all kicked off, we headed up the short staircase and popped out into the grand landscape of Goodison. The Gwladys Street End is one of two stands designed by Archibald Leitch, the Scotsman who traveled England and Scotland in the first half of the 20th century building spectator enclosures at many of those nations’ greatest grounds: Highbury, Stamford Bridge, Celtic Park, Ibrox, Villa Park, Craven Cottage, Hampden Park, Old Trafford, and Anfield. When you head down to the bottom of the Gwladys, near the pitch, you can get a clear view of the Bullens Road Stand with its famous crisscross pattern on the second tier, a Leitch trademark. That’s where both Richie and Rob sit now, though for a long time, Rob stood here in the Gwladys Street.

“That was where I'd go in the 80s, when Everton were winning stuff,” he said.

While that’s certainly changed, and the terracing on the Gwladys lower has given way to seating, one thing hasn’t: Everybody stays standing the whole time. In our seats near the back, where the overhang hung low and the thick blue beam rose in front of us to meet it, the pitch was obscured entirely when the players were first walking out on the pitch and the Premier League anthem played. A collection of tifos in white and blue and yellow descended over the letterbox window for the duration of the opening ceremonies. All around, they began to sing the old hymns of the Gwladys and some newer ones, too. Soon enough, the other stands joined in.

Over to the right looking out from the Gwladys is the Goodison Road Stand—the Main Stand—with its skinny white pillars rising up to support it, finished in 1971 after the original double-decker designed by Archibald Leitch was knocked down to make room.

Across from that is the Bullens Road, which will be one year short of the century mark when the club abandons Goodison this summer. The stand was there when Dixie Dean scored his 60th goal back in 1928, and it has witnessed every triumph and disaster on the Goodison pitch since. It was first built in 1905 for a total cost of £3,000, then redesigned by Leitch in the ‘20s. The seats in the Paddock, at the foot of the stand, are in timeworn wood, the royal blue paint fading in places even with generations of touch-ups. The floorboards throughout the stand are wooden, and the thunking stomp of supporters on them is a sound that will soon be lost to football history.

And finally, there’s the Park End, opposite the Gwladys on the far side behind the other goal. Originally named for Stanley Park, which is across the road behind it, it was built new in 1994 following the Taylor Report in a cantilever style that means it’s the only one of the four without obstructed views. It’s also the only stand that’s a single tier, rather than the doubles everywhere else.

In sum, it’s four different stands built at four different times in four different designs.

“That is the piecemeal approach to football architecture that we’re used to,” Jon Champion, the acclaimed commentator for NBC and ESPN, said on The Football Weekend podcast last year. “It’s only really in the last 35 years that we’ve had brand-new stadiums built complete from scratch. One by one, the [old ones] are disappearing, and one of my sad days coming up will be the last game at Goodison Park.”

Because, as the commentators well know, Goodison’s idiosyncrasies go beyond wooden floors and obstructed views.

“There is video on social media of the climb to the gantry at Goodison Park,” Champion said, “which involves: walking up the inside of the old Bullens Road Stand, through a little door that’s about four feet high at the back, up a vertical ladder on the outside of the stand, onto the roof, right across the roof, and then through a hatch—doorway—down a vertical ladder onto a suspended steel platform beneath the roof. It’s the most magnificent view when you get there….It’s all about the view. It doesn’t matter about the inherent dangers in getting there.”

The only issue, Champion said, is that there’s no toilet. “When I was in my 20s, it didn’t really bother me. Now I’m in my 50s, it’s a little bit more of a concern, particularly on a cold day.” It proved a disastrous feature for one of Champion’s old colleagues in broadcasting, the since-departed Gerald Sinstadt.

“On one particular day in the depths of December, he was up there and he was caught short. He required toilet facilities,” Champion said. “There was still about 45 minutes of the game to go, and he suffered the ultimate indignity, because the Everton ground staff arranged for a bucket to be winched up onto the gantry in full view of the entire Goodison Park congregation, who then watched from afar whilst he filled this bucket, which was then painfully winched down.”

There will be no such architectural peculiarities, or the stories they spawn, in the new place. There couldn’t be even if they were wanted. It’s down to the very nature of Goodison’s story, spanning from the days before radio through the television revolution to the digital age, that jerry-rigged solutions became necessary. They didn’t have a gantry because they didn’t need a gantry, and then they needed one so they had to make it work somehow. This place was built in layers, like a street in an old quarter of Rome. The pieces were made to fit together because they just had to fit. And unlike other old football churches that might stick around, this one is big. This one is a cathedral.

“It holds nearly 40,000 people. It has staged World Cup semifinals,” Champion said. “It’s the last of the great signature old stadiums…It will be a sad day indeed when we walk out of there for the last time.”

Outside, the warmth of the stand melts away in the damp cold of Liverpool in January as the throngs drift down Gwladys Street and around the corner at St. Luke’s to head down Goodison Road. Across from the stadium are Chinese takeaways and a newsstand and even a hair salon.

But the main landmark across from the giant murals of Bob Latchford and Dixie Dean is the Winslow Hotel, the People’s Pub. Its red bricks are laced with lines of blue to match the stadium across the way, and when you walk in, the warmth comes washing over you. Your eyeglasses, if you’ve got ‘em, might even fog up with all the breath and chat and sheer humanity inside. You can see what draws people in from the dour days outside, when the sky hangs low over northern England and often, the sun never seems to rise through the cloud cover.

“I came over to take over the Winslow in 2014,” says Dave Bond, an Irishman who’s run the hotel for the last decade. “1st of March opening. That's the date that Dixie Dean died. 1 March 1980. He died of a heart attack in the ground watching Everton play Liverpool. And his image is over the door of the Winslow. It's been there for 100 years, on the signage.”

Built in 1886, the Winslow predates Goodison Park by six years. The signage has been there since the 1800s, which is why Dave says they’ve kept “The Winslow Hotel” as a trade name despite there no longer being rooms to stay in. “From the moment the first ball was kicked in 1892, right up until the end of this season when the last ball gets kicked by the senior team, Evertonians have been coming to the Winslow as part of their matchday ritual,” Dave said.

There was a period where the Winslow was lost following some poor management. From 2012 to 2014, it was shuttered, and before it reopened Dave and the ownership group gave the interior a “massive makeover”: New floors, paint and varnish, new bathroom tiles and toilets. There are murals of famous Evertonians and their greatest quotes about the club all over, painted by a local Evertonian artist. The tiling heading into one bathroom has “EFC” mosaiced in. Pretty much everywhere you look, it’s blue and white.

“I started supporting Everton as a nine year old in 1976. That’s where the love affair started for me,” Dave said. He rarely got to go to Goodison, though, until he moved back to Europe—following a stint in New York—in the 1990s. “I lived in Germany and I used to pop over to Goodison. Well, I popped over about five or six times. And the mad thing about that is I didn't know anything about the Winslow. I remember walking down Goodison Road and going, ‘Oh, this looks a good place. I’ll pop in here for a pint.’ Little did I know that all these years later I would end up running the place.”

He remembers the famous recent days in this sacred place for the Evertonians, like the win over Bournemouth to keep them up in 2023. “The atmosphere in the pub from when we opened in the morning was absolutely electric, and the game was on TV, so we were packed during the game,” Dave said. “People were coming in just to watch it, to be around the atmosphere.” For a 15-minute spell in the second half, when Leicester City took the lead elsewhere and Everton hadn’t, the Toffees were going down. The outpouring of relief when they survived, avoiding a first relegation since 1951, made for a raucous party in the Winslow.

But now Dave fears what days and nights at this place will look like. He acknowledges that Goodison isn’t big enough, and there’s nowhere to build around it in an area surrounded by housing blocks. “It's going to bring in that much more revenue for the club,” he said. “Which, sadly, in today's footballing world, it's all about revenue, isn't it?”

The ramifications for his business, though, could be catastrophic. They’re going to try running coaches from the Winslow to the new stadium to see if they can remain part of the matchday experience. It’s only a couple of miles away. “But hand on heart,” he says, “I think business is going to drop off by up to 70, 80 percent.”

The ownership group has put in an application for planning permission with the local authorities to convert the upstairs into guest rooms, which would return the Winslow Hotel to its roots. (The Hotel hasn’t hosted guests since the early 20th century, sometime around the First World War, though Dave says the timeline there is foggy.) Other businesses in the Goodison ecosystem, the civic and cultural habitat anchored around Everton Football Club—the chippies, the Chinese joints, the many other bars and pubs in the surrounding blocks—won’t have much of anything else to fall back on. They aren’t likely to survive when Everton move to the dock.

But for Dave and surely some of those business owners, it won’t be chiefly financial. “What I'm going to miss the most is the matchday experience. Everything else that goes around throughout the year is only just, for me, second fiddle. That adrenaline rush, that buzz of having 800 to 1,000 fans just bombard you, and the feel good factor when you get a win afterwards. It's just—I'm gonna miss all that.”

Tottenham’s Son Heung-min fluffed a chance to equalize in front of the Gwladys Street End after 25 minutes, and the whole section grimaced, winced, gasped. At the very beginning of 2025, the Evertonians held everything tenuously, from their membership in the world’s richest football league to a 1-0 lead at home. The 3-0 advantage that David Moyes and his team carried into halftime was almost incomprehensible to the blue-and-white crowds chatting and sipping out in the concourse. What happened after the second half kicked off was more familiar.

Everton drove down towards the Gwladys Street End a few times and pieced together some half-chances, but then the game started to run against them. James Maddison began to get involved for the visitors, pulling some strings, and then, on 77 minutes, Dejan Kulusevski latched onto a loose ball in the box with Everton stretched and stressed, lifting it deftly over everyone and into the net to get a goal back. The old Evertonian, Richarlison, got one late on to really get people worried. Hands were on heads throughout the final period. People shifted back and forth in place and groaned.

This is a fanbase that’s battered and bruised at this point. “Plenty of hard luck stories,” Richie said. “Plenty of them. But we still keep on coming though. Got to. It’s in our blood.” Forget those storied days of the ‘80s—they’re far away now even from David Moyes’ first tenure, when they were consistently competing for a place in the Top Six.

“My own son, he's 32 in November,” Richie said, “and he's not seen us win it. He was only a baby when we won the cup in ‘95. A lot of fans have not seen us pick silverware up. It took me 18 years. But that's what we need. Anything, any cup.”

And there is a growing belief—a consensus, really—that they must move to do that, even if they’re selling out every game now in a way they often didn’t when they were good.

“Everton cannot compete, Everton cannot ultimately exist, in that beautiful place,” Roger Bennett says of Goodison. “Every home game we have, we fall further and further behind any club that has a commercial infrastructure that Goodison Park can never match.

“It's a grand old place, a grand old home. It's also an old shack at this point. And it's almost a connection to a deep and rich history that is irreplaceable. It's a connection to a grander time when Everton really were a glorious team. That’s what I feel when I’m there.”

It’s about the personal heritage, too. Rob said that his father and grandfather and great-grandfather walked the same steps he does every time he goes to watch Everton. And it isn’t all history.

“That’s the thing with Goodison, it’s a lot of faces,” Richie said. “You might not know their names. I was just thinking, coming here this morning—the security guards, the bar staff in the Winslow, the people [selling] the scarves and the badges in the stalls outside. It's just—it's like a home. Like a sanctuary. This is our church.”

“It’s so iconic, it should really be listed,” he continued. “I'm surprised it's not listed, especially the Bullens Road.” But all that building and rebuilding across the four stands that’s lent the stadium its charm has also disqualified it from landmark status. “And look, land makes money, doesn’t it?” Richie said. “And money makes the world go around. And that's why we've got to move.”

With so much to sacrifice, the stakes couldn’t be higher. As you speak to Evertonians about the new ground on the river, you often hear the same phrase, a kind of prayer they speak to the football gods about what might happen at their new home on “the royal blue Mersey.”

Down at the Bramley Moore Dock, Everton’s new stadium rises up in the fog hanging over the River Mersey. The blue lighting that rings the structure below the roof glows in the damp night.

It’s behind slatted silver gates, newly installed between the old stone turrets of the docklands constructed here by Jesse Hartley and opened by John Bramley-Moore, then chairman of the Liverpool docks committee. The riverfront has been filled in to create the foundation for the stadium, and the whole area inside the gates has been generally transformed, but some vestigial structures still remain from a past life.

There’s a pub across the street, Regent Road, and on the sign outside it says, “FREE HOUSE — EST. 1758.” It’s called, aptly, the Bramley Moore. Inside, it’s a classic local: wood panels, dark blue carpet with a recurring gold and red medallion design. A couple of brown painted metal pillars rise up in the middle of the room. There’s a pool table in the back, and the seating is arranged in an arc of red-cushioned banquettes that shapes the heart of the space.

Behind the bar, Rachel Flood is chatting with regulars on the stools across. Her mom, Angela Burns, joined the Bramley Moore 33 years ago as a barmaid. Eventually, she came to own the place. For many decades, it was seamen from the big steamships that came in here, back when Liverpool was a force of nature in international shipping. Then it was the dockworkers and local craftsmen, Rachel said, once the major seafaring business went away from Liverpool and everything got more difficult. Still, the metalworkers and machinists and mechanics brought in enough business to just about keep the place going, to keep the Bramley Moore alive. It survived COVID-19, and now, Rachel said, they can scarcely believe it.

Suddenly, a blue bolt in the fog: a brand new stadium across the street that will attract 50,000 people and more for so many weeks of the year. This has always been a bar that draws Evertonians—though not exclusively—but soon it will be a serious Everton haunt, at least on matchdays. They hope to keep their character as a good honest local for everyone, somewhere to come for a Guinness on a Tuesday, but there’s no denying it: the new stadium will change everything.

Other bars and restaurants will surely spring up around here, even if the stadium is set to feature tons of on-campus pubs and hospitality, but not much else is blue yet. It’s brown under the gray skies, old warehouses and industrial buildings weathered and beaten. Down the road from the Bramley Moore, a giant rectangular brick structure, once a storehouse or a factory space, sits with a gaping hole in the roof.

The regeneration along the docks is a freighted prospect for Liverpool, a port town that lost its ships and had to find a new way of being. So, too, will Everton.

“Ultimately, you're catching the club at an incredible time,” Roger Bennett said. “What’s old is new. David Moyes is back, and it's an amazing time to be alive. It's an amazing time to be a Blue. We are currently the Premier League team with the oldest stadium in club football and the newest stadium in club football. I'm grateful for the past, I'm grateful for the memories, and I can't wait to build new ones.” On the banks of the royal blue Mersey.⚽︎

———————————

Photos by Jack Holmes (with the exception of the Bramley-Moore Dock aerial shot, from Getty)

Thanks to reader Dennis Stevens for pointing out that Everton won the first of their nine league titles while still at Anfield Road, before they moved to Goodison! The story has been updated.

Brilliant Jack regards Richie

9 League titles? Surely, you recall that the very first League title in 1891 was at our previous ground!